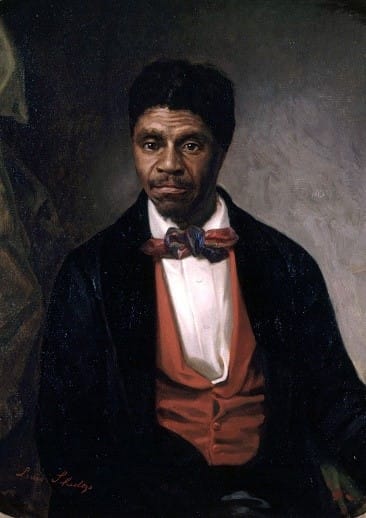

In his majority opinion in the case of Dred Scott (1857), Chief Justice Roger B. Taney, in what is widely considered the worst Supreme Court decision in our nation’s history, infamously wrote:

“We think [people of African ancestry] are not… included, and were not intended to be included, under the word “citizens” in the Constitution… [and are] altogether unfit to associate with the white race, either in social or political relations; and so far inferior, that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect; and that the negro might justly and lawfully be reduced to slavery for his benefit…”

Referring to the Declaration of Independence’s claim that, “all men are created equal,” Taney asserted: “it is too clear for dispute, that the enslaved African race were not intended to be included, and formed no part of the people who framed and adopted this declaration…”

Abolitionists like Frederick Douglass to anti-slavery Republicans like Abraham Lincoln and Charles Sumner roundly rejected Taney. Much more recently, Chief Justice Roberts referred to it as the worst example of judicial activism.

Yet Taney’s view permeates 400 years of American history, and tragically finds current expression in White supremacist circles: namely the belief that Black people are unequal and unworthy of human dignity.

I found historian and President of Rutgers Jonathan Holloway’s February 11, 2021 op-ed in the New York Times, Isn’t 400 Years Enough? to be a crisp historical overview, yet also a challenge to me as I tend towards moderation and the “evolution of revolution” in my activism. It pushes me to recall the assessment of the legendary Black scholar-activist W.E.B. DuBois who in 1935 described the period of Reconstruction as “The slave went free; stood a brief moment in the sun; then moved back again toward slavery.”

DuBois was referencing that after a decade of racial equity and Black political and economic progress, a backlash emerged leading to 80 years of renewed oppression and denial of full equality. An intellectual lie known as “The Lost Cause”, which framed slavery as benign and the southern cause as noble, culturally endorsed this retrogression.

Tragically, the past 50 years, and particularly the past few years, have witnessed a similar backlash of populist White grievance against the movements of the mid-50s to mid-70s.

These thoughts call me to greater focus, historically and in the present. According to data cited by Ibram X. Kendi, last summer witnessed over 8,000 demonstrations for Black Lives and racial justice. These actions suggest a potential pivot and shift in the moral arc of the universe. But history tells me that we falter, and that as King wrote so powerfully in Letter From Birmingham Jail – a direct challenge to White moderates of that era – “Wait” has almost always meant “Never.”

In his remarks at Gettysburg, Abraham Lincoln addressed the proposition that all men are created equal and called on Americans to make it “our great task” to realize the Declaration’s aspirational goals. A century later, Martin Luther King, Jr referenced that call in the first portion of his speech at the March on Washington. Those often forgotten first 11 minutes offer an historic lesson and a set of demands, and King’s view that the Declaration was “a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir.” He went on to offer a “but”:

“It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note, insofar as her citizens of color are concerned. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check, a check which has come back marked “insufficient funds… But we refuse to believe that the bank of justice is bankrupt. We refuse to believe that there are insufficient funds in the great vaults of opportunity of this nation. And so, we’ve come to cash this check, a check that will give us upon demand the riches of freedom and the security of justice.”

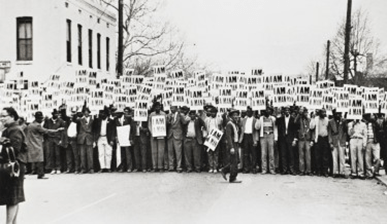

After experiencing violent backlash and modest success in Chicago, King’s final campaign, The Poor People’s Campaign, found its focus during 1968 in Memphis. Defending the rights of sanitation workers, King proclaimed “Our society must come to respect the sanitation worker. He is as significant as the physician, for if he doesn’t do his job, disease is rampant.” King’s emphasis on human dignity regardless of economic station in life brings me back to Holloway who frames his piece with three phases of development in the conceptualization of Black lives in America, asking….

- What does it mean to be human?

- What does it mean to be a citizen?

- What does it mean to be civilized?

In short, at the heart of White supremacism and racism is the dehumanization of other people, or as seen in Memphis, a refusal to recognize Black sanitation workers as men.

Ibram X. Kendi, in a recent talk hosted by Carnegie Mellon University, responded to a request to define racism and anti-racism with the following:

Racism and antiracism are inherently institutional, structural, and systemic… I define racism as a powerful collection of policies that lead to racial inequity and are substantiated by ideas of racial hierarchy… In other words, a series of policies that cause Black people to be twice as likely to be unemployed, and then the people commonly believing Black people are more likely to be unemployed because they believe Black people are lazy, don’t want to work, there’s something wrong with Black people. That’s racism.

By contrast, anti-racism is a powerful collection of policies that lead to racial equity and are substantiated by ideas of racial equality. In other words, there’s equity between groups and people see that equity as something that should be the case because they see those different racialized groups as equals.[1]

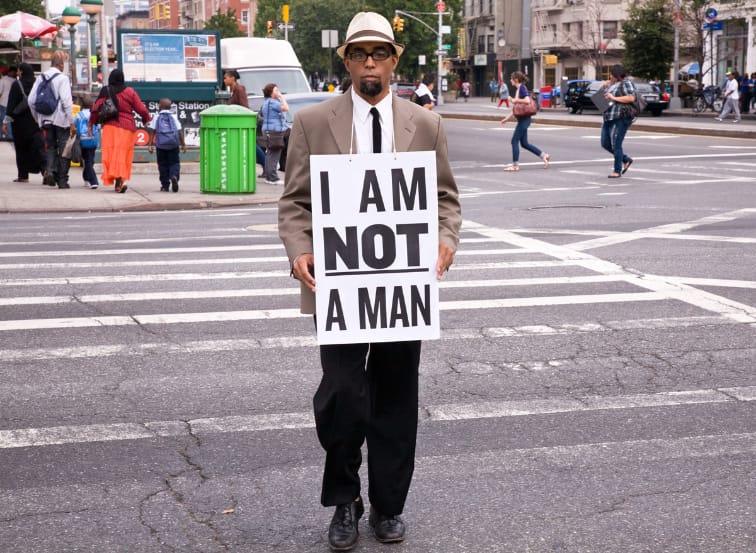

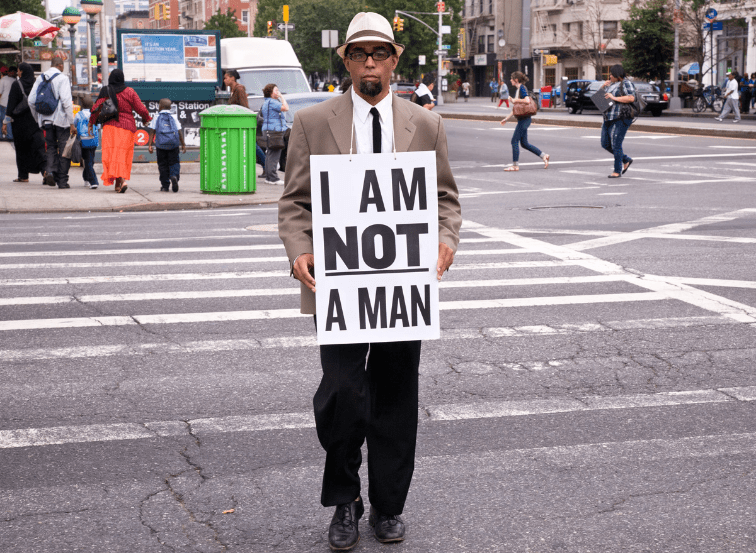

Without a fundamental shift in ideas, policies will not change. Performance artist Dred Scott makes us confront the contemporary need to dignify the humanity of Black people.

For over 30 years, artist and street performer Dred Scott has been challenging Americans to examine current inequities, often through the lens of history, to, in his words, “look towards an era without exploitation or oppression.”

His play on the sanitation workers’ motto reminds us, as Holloway does, that we still have progress to make in achieving the full recognition of the basic humanity of Black men and women.

Holloway references James Baldwin, which took my mind back 30 years when I first saw a documentary produced by Ken Burns tracing the history of and multiple meanings of The Statue of Liberty. Particularly if you identify as White, listen to James Baldwin’s reflection in this five-minute video, which includes Burns’ added commentary to frame Baldwin’s understanding of “What is Liberty?” Ken Burns: Our monuments are representations of myth, not fact | Opinion. (from “Statue of Liberty” (1985)).

Let’s heed Holloway’s call to appreciate the many people who have contributed their lives, dignity and humanity to make this nation a more perfect union, and to be more militant in our calls that justice delayed is justice denied. We may be living in our own “moment in the sun.” Let’s not it slip back into darkness. Indeed, 400 years has been more than enough.

This opinion article was written by Pete DiNardo, a high school teacher in Mt. Lebanon and founding member of M.O.R.E and its Anti-Racism Education Committee (AREC), and originally published by M.O.R.E on April 5, 2021.

1Ibram X. Kendi. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Keynote Lecture: A Conversation with Dr. Ibram X. Kendi, Carnegie Mellon University, February 10, 2021